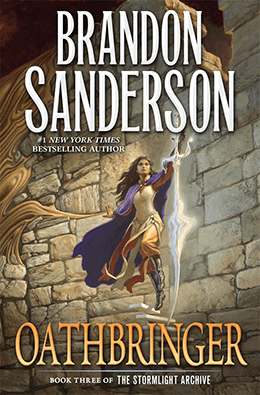

Start reading Oathbringer, the new volume of Brandon Sanderson’s Stormlight Archive epic, right now. For free!

Tor.com is serializing the much-awaited third volume in the Stormlight Archive series every Tuesday until the novel’s November 14, 2017 release date.

Every installment is collected here in the Oathbringer index.

Need a refresher on the Stormlight Archive before beginning Oathbringer? Here’s a summary of what happened in Book 1: The Way of Kings and Book 2: Words of Radiance.

Spoiler warning: Comments will contain spoilers for previous Stormlight books, other works that take place in Sanderson’s cosmere (Elantris, Mistborn, Warbreaker, etc.), and the available chapters of Oathbringer, along with speculation regarding the chapters yet to come.

Chapter 10

Distractions

Perhaps my heresy stretches back to those days in my childhood, where these ideas began.

—From Oathbringer, preface

Kaladin leaped from a hilltop, preserving Stormlight by Lashing himself upward just enough to give him some lift.

He soared through the rain, angled toward another hilltop. Beneath him, the valley was clogged with vivim trees, which wound their spindly branches together to create an almost impenetrable wall of forestation.

He landed lightly, skidding across the wet stone past rainspren like blue candles. He dismissed his Lashing, and as the force of the ground reasserted itself, he stepped into a quick march. He’d learned to march before learning the spear or shield. Kaladin smiled. He could almost hear Hav’s voice barking commands from the back of the line, where he helped stragglers. Hav had always said that once men could march together, learning to fight was easy.

“Smiling?” Syl said. She’d taken the shape of a large raindrop streaking through the air beside him, falling the wrong way. It was a natural shape, but also completely wrong. Plausible impossibility.

“You’re right,” Kaladin said, rain dribbling down his face. “I should be more solemn. We’re chasing down Voidbringers.” Storms, how odd it sounded to say that.

“I didn’t intend it as a reprimand.”

“Hard to tell with you sometimes.”

“And what was that supposed to mean?”

“Two days ago, I found that my mother is still alive,” Kaladin said, “so the position is not, in fact, vacant. You can stop trying to fill it.”

He Lashed himself upward slightly, then let himself slide down the wet stone of the steep hill, standing sideways. He passed open rockbuds and wiggling vines, glutted and fat from the constant rainfall. Following the Weeping, they’d often find as many dead plants around the town as they did after a strong highstorm.

“Well, I’m not trying to mother you,” Syl said, still a raindrop. Talking to her could be a surreal experience. “Though perhaps I chide you on occasion, when you’re being sullen.”

He grunted.

“Or when you’re being uncommunicative.” She transformed into the shape of a young woman in a havah, seated in the air and holding an umbrella as she moved along beside him. “It is my solemn and important duty to bring happiness, light, and joy into your world when you’re being a dour idiot. Which is most of the time. So there.”

Kaladin chuckled, holding a little Stormlight as he ran up the side of the next hill, then skidded down into the next valley. This was prime farmland; there was a reason why the Akanny region was prized by Sadeas. It might be a cultural backwater, but these rolling fields probably fed half the kingdom with their lavis and tallew crops. Other villages focused on raising large passels of hogs for leather and meat. Gumfrems, a kind of chull-like beast, were less common pasture animals harvested for their gemhearts, which—though small—allowed Soulcasting of meat.

Syl turned into a ribbon of light and zipped in front of him, making loops. It was difficult not to feel uplifted, even in the gloomy weather. He’d spent the entire sprint to Alethkar worrying—and then assuming—that he’d be too late to save Hearthstone. To find his parents alive… well, it was an unexpected blessing. The type his life had been severely lacking.

So he gave in to the urging of the Stormlight. Run. Leap. Though he’d spent two days chasing the Voidbringers, Kaladin’s exhaustion had faded. There weren’t many empty beds to be found in the broken villages he passed, but he had been able to find a roof to keep him dry and something warm to eat.

He’d started at Hearthstone and worked his way outward in a spiral— visiting villages, asking after the local parshmen, then warning people that the terrible storm would return. So far, he hadn’t found a single town or village that had been attacked.

Kaladin reached the next hilltop and pulled to a stop. A weathered stone post marked a crossroads. During his youth, he’d never gotten this far from Hearthstone, though he wasn’t more than a few days’ walk away.

Syl zipped up to him as he shaded his eyes from the rain. The glyphs and simple map on the stone marker would indicate the distance to the next town—but he didn’t need that. He could make it out as a smudge in the gloom. A fairly large town, by local standards.

“Come on,” he said, starting down the hillside.

“I think,” Syl said, landing on his shoulder and becoming a young woman, “I would make a wonderful mother.”

“And what inspired this topic?”

“You’re the one who brought it up.”

In comparing Syl to his mother for nagging him? “Are you even capable of having children? Baby spren?”

“I have no idea,” Syl proclaimed.

“You call the Stormfather… well, Father. Right? So he birthed you?”

“Maybe? I think so? Helped shape me, is more like it. Helped us find our voices.” She cocked her head. “Yes. He made some of us. Made me.”

“So maybe you could do that,” Kaladin said. “Find little, uh, bits of the wind? Or of Honor? Shape them?”

He used a Lashing to leap over a snarl of rockbuds and vines, and startled a pack of cremlings as he landed, sending them scuttling away from a nearly clean mink skeleton. Probably the leavings of a larger predator.

“Hmmm,” Syl said. “I would be an excellent mother. I’d teach the little spren to fly, to coast the winds, to harass you.…”

Kaladin smiled. “You’d get distracted by an interesting beetle and fly off, leaving them in a drawer somewhere.”

“Nonsense! Why would I leave my babies in a drawer? Far too boring. A highprince’s shoe though…”

He flew the remaining distance to the village, and the sight of broken buildings at the western edge dampened his mood. Though the destruction continued to be less than he’d feared, every town or village had lost people to the winds or the terrible lightning.

This village—Hornhollow, the map called it—was in what once would have been considered an ideal location. The land here dipped into a depression, and a hill to the east cut the brunt of the highstorms. It held about two dozen structures, including two large storm sanctuaries where travelers could stay—but there were also many outer buildings. This was the highprince’s land, and an industrious darkeyes of high enough nahn could get a commission to work an unused hill out by itself, then keep a portion of the crop.

A few sphere lanterns gave light to the square, where people had gathered for a town meeting. That was convenient. Kaladin dropped toward the lights and held his hand to the side. Syl formed there by unspoken command, taking the shape of a Shardblade: a sleek, beautiful sword with the symbol of the Windrunners prominent on the center, with lines sweeping off it toward the hilt—grooves in the metal that looked like flowing tresses of hair. Though Kaladin preferred a spear, the Blade was a symbol.

Kaladin hit the ground in the center of the village, near its large central cistern, used to catch rainwater and filter away the crem. He rested the Sylblade on his shoulder and stretched out his other hand, preparing his speech. People of Hornhollow. I am Kaladin, of the Knights Radiant. I have come—

“Lord Radiant!” A portly lighteyed man stumbled out of the crowd, wearing a long raincloak and a wide-brimmed hat. He looked ridiculous, but it was the Weeping. Constant rain didn’t exactly encourage heights of fashion.

The man clapped his hands in an energetic motion, and a pair of ardents stumbled up beside him, bearing goblets full of glowing spheres. Around the perimeter of the square, people hissed and whispered, anticipationspren flapping in an unseen wind. Several men held up small children to get a better look.

“Great,” Kaladin said softly. “I’ve become a menagerie act.”

In his mind, he heard Syl giggle.

Well, best to put on a good show of it. He lifted the Sylblade high overhead, prompting a cheer from the crowd. He would have bet that most of the people in this square used to curse the name of the Radiants, but none of that was manifest now in the people’s enthusiasm. It was hard to believe that centuries of mistrust and vilification would be forgotten so quickly. But with the sky breaking and the land in turmoil, people would look to a symbol.

Kaladin lowered his Blade. He knew all too well the danger of symbols. Amaram had been one to him, long ago.

“You knew of my coming,” Kaladin said to the citylord and the ardents. “You’ve been in contact with your neighbors. Have they told you what I’ve been saying?”

“Yes, Brightlord,” the lighteyed man said, gesturing eagerly for him to take the spheres. As he did so—replacing them with spent ones he’d traded for previously—the man’s expression fell noticeably.

Expected me to pay two for one as I did at the first few towns, did you? Kaladin thought with amusement. Well, he dropped a few extra dun spheres in. He’d rather be known as generous, particularly if it helped word spread, but he couldn’t halve his spheres each time he went through them.

“This is good,” Kaladin said, fishing out a few small gemstones. “I can’t visit every holding in the area. I need you to send messages to each nearby village, carrying words of comfort and command from the king. I will pay for the time of your runners.”

He looked out at the sea of eager faces, and couldn’t help but remember a similar day in Hearthstone where he and the rest of the townspeople had waited, eager to catch a glimpse of their new citylord.

“Of course, Brightlord,” the lighteyed man said. “Would you wish to rest now, and take a meal? Or would you rather visit the location of the attack immediately?”

“Attack?” Kaladin said, feeling a spike of alarm.

“Yes, Brightlord,” the portly lighteyes said. “Isn’t that why you’re here?

To see where the rogue parshmen assaulted us?”

Finally! “Take me there. Now.”

They’d attacked a grain storage just outside town. Squashed between two hills and shaped like a dome, it had weathered the Everstorm without so much as a loosed stone. That made it a particular shame that the Voidbringers had ripped open the door and pillaged what was inside.

Kaladin knelt within, flipping over a broken hinge. The building smelled of dust and tallew, but was too wet. Townspeople who would suffer a dozen leaks in their bedroom would go to great expense to keep their grain dry.

It felt odd to not have the rain on his head, though he could still hear it pattering outside.

“May I continue, Brightlord?” the ardent asked him. She was young, pretty, and nervous. Obviously she didn’t know where he fit into the scheme of her religion. The Knights Radiant had been founded by the Heralds, but they were also traitors. So… he was either a divine being of myth or a cretin one step above a Voidbringer.

“Yes, please,” Kaladin said.

“Of the five eyewitnesses,” the ardent said, “four, um, independently counted the number of attackers at… fifty or so? Anyway, it’s safe to say that they’ve got large numbers, considering how many sacks of grain they were able to carry away in such a short time. They, um, didn’t look exactly like parshmen. Too tall, and wearing armor. The sketch I made… Um…”

She tried showing him her sketch again. It wasn’t much better than a child’s drawing: a bunch of scribbles in vaguely humanoid shapes.

“Anyway,” the young ardent continued, oblivious to the fact that Syl had landed on her shoulder and was inspecting her face. “They attacked right after first moonset. They had the grain out by middle of second moon, um, and we didn’t hear anything until the change of guard happened. Sot raised the alarm, and that chased the creatures off They only left four sacks, which we moved.”

Kaladin took a crude wooden cudgel off the table next to the ardent. The ardent glanced at him, then quickly looked back to her paper, blushing. The room, lit by oil lamps, was depressingly hollow. This grain should have gotten the village to the next harvest.

To a man from a farming village, nothing was more distressing than an empty silo at planting time.

“The men who were attacked?” Kaladin said, inspecting the cudgel, which the Voidbringers had dropped while fleeing.

“They’ve both recovered, Brightlord,” the ardent said. “Though Khem has a ringing in his ear he says won’t go away.”

Fifty parshmen in warform—which was what the descriptions sounded most like to him—could easily have overrun this town and its handful of militia guards. They could have slaughtered everyone and taken whatever they wished; instead, they’d made a surgical raid.

“The red lights,” Kaladin said. “Describe them again.”

The ardent started; she’d been looking at him. “Um, all five witnesses mentioned the lights, Brightlord. There were several small glowing red lights in the darkness.”

“Their eyes.”

“Maybe?” the ardent said. “If those were eyes, it was only a few. I went and asked, and none of the witnesses specifically saw eyes glowing—and Khem got a look right in one of the parshmen’s faces as they struck him.”

Kaladin dropped the cudgel and dusted off his palms. He took the sheet with the picture on it out of the young ardent’s hands and inspected it, just for show, then nodded to her. “You did well. Thank you for the report.”

She sighed, grinning stupidly.

“Oh!” Syl said, still on the ardent’s shoulder. “She thinks you’re pretty!”

Kaladin drew his lips to a line. He nodded to the woman and left her, striking back into the rain toward the center of town.

Syl zipped up to his shoulder. “Wow. She must be desperate living out here. I mean, look at you. Hair that hasn’t been combed since you flew across the continent, uniform stained with crem, and that beard.”

“Thank you for the boost of confidence.”

“I guess when there’s nobody about but farmers, your standards really drop.”

“She’s an ardent,” Kaladin said. “She’d have to marry another ardent.”

“I don’t think she was thinking about marriage, Kaladin…” Syl said, turning and looking backward over her shoulder. “I know you’ve been busy lately fighting guys in white clothing and stuff, but I’ve been doing research. People lock their doors, but there’s plenty of room to get in underneath. I figured, since you don’t seem inclined to do any learning yourself, I should study. So if you have questions…”

“I’m well aware of what is involved.”

“You sure?” Syl asked. “Maybe we could have that ardent draw you a picture. She seems like she’d be really eager.”

“Syl…”

“I just want you to be happy, Kaladin,” she said, zipping off his shoulder and running a few rings around him as a ribbon of light. “People in relationships are happier.”

“That,” Kaladin said, “is demonstrably false. Some might be. I know a lot who aren’t.”

“Come on,” Syl said. “What about that Lightweaver? You seemed to like her.”

The words struck uncomfortably close to the truth. “Shallan is engaged to Dalinar’s son.”

“So? You’re better than him. I don’t trust him one bit.”

“You don’t trust anyone who carries a Shardblade, Syl,” Kaladin said with a sigh. “We’ve been over this. It’s not a mark of bad character to have bonded one of the weapons.”

“Yes, well, let’s have someone swing around the corpse of your sisters by the feet, and we’ll see whether you consider it a ‘mark of bad character’ or not. This is a distraction. Like that Lightweaver could be for you…”

“Shallan’s a lighteyes,” Kaladin said. “That’s the end of the conversation.”

“But—”

“End,” he said, stepping into the home of the village lighteyes. Then he added under his breath, “And stop spying on people when they’re being intimate. It’s creepy.”

The way she spoke, she expected to be there when Kaladin… Well, he’d never considered that before, though she went with him everywhere else. Could he convince her to wait outside? She’d still listen, if not sneak in to watch. Stormfather. His life just kept getting stranger. He tried— unsuccessfully—to banish the image of lying in bed with a woman, Syl sitting on the headboard and shouting out encouragement and advice.…

“Lord Radiant?” the citylord asked from inside the front room of the small home. “Are you well?”

“Painful memory,” Kaladin said. “Your scouts are certain of the direction the parshmen went?”

The citylord looked over his shoulder at a scraggly man in leathers, bow on his back, standing by the boarded-up window. Trapper, with a writ from the local highlord to catch mink on his lands. “Followed them half a day out, Brightlord. They never deviated. Straight toward Kholinar, I’d swear to Kelek himself.”

“Then that’s where I’m going as well,” Kaladin said.

“You want me to lead you, Brightlord Radiant?” the trapper asked.

Kaladin drew in Stormlight. “Afraid you’d just slow me down.” He nodded to the men, then stepped out and Lashed himself upward. People clogged the road and cheered from rooftops as he left the town behind.

The scents of horses reminded Adolin of his youth. Sweat, and manure, and hay. Good scents. Real scents.

He’d spent many of those days, before he was fully a man, on campaign with his father during border skirmishes with Jah Keved. Adolin had been afraid of horses back then, though he’d never have admitted it. So much faster, more intelligent, than chulls.

So alien. Creatures all covered in hair—which made him shiver to touch—with big glassy eyes. And those hadn’t even been real horses. For all their pedigree breeding, the horses they’d rode on campaign had just been ordinary Shin Thoroughbreds. Expensive, yes. But by definition, therefore, not priceless.

Not like the creature before him now.

They were housing the Kholin livestock in the far northwest section of the tower, on the ground floor, near where winds from outside blew along the mountains. Some clever constructions in the hallways by the royal engineers had ventilated the scents away from the inner corridors, though that left the region quite chilly.

Gumfrems and hogs clogged some rooms, while conventional horses stabled in others. Several even contained Bashin’s axehounds, animals who never got to go on hunts anymore.

Such accommodations weren’t good enough for the Blackthorn’s horse. No, the massive black Ryshadium stallion had been given his own field. Large enough to serve as a pasture, it was open to the sky and in an enviable spot, if you discounted the scents of the other animals.

As Adolin emerged from the tower, the black monster of a horse came galloping over. Big enough to carry a Shardbearer without looking small, Ryshadium were often called the “third Shard.” Blade, Plate, and Mount.

That didn’t do them justice. You couldn’t earn a Ryshadium simply by defeating someone in combat. They chose their riders.

But, Adolin thought as Gallant nuzzled his hand, I suppose that was how it used to be with Blades too. They were spren who chose their bearers.

“Hey,” Adolin said, scratching the Ryshadium’s snout with his left hand. “A little lonely out here, isn’t it? I’m sorry about that. Wish you weren’t alone any—” He cut off as his voice caught in his throat.

Gallant stepped closer, towering over him, but somehow still gentle.

The horse nuzzled Adolin’s neck, then blew out sharply.

“Ugh,” Adolin said, turning the horse’s head. “That’s a scent I could do without.” He patted Gallant’s neck, then reached with his right hand into his shoulder pack—before a sharp pain from his wrist reminded him yet again of his wound. He reached in with the other hand and took out some sugar lumps, which Gallant consumed eagerly.

“You’re as bad as Aunt Navani,” Adolin noted. “That’s why you came running, isn’t it? You smelled treats.”

The horse turned his head, looking at Adolin with one watery blue eye, rectangular pupil at the center. He almost seemed… offended.

Adolin often had felt he could read his own Ryshadium’s emotions. There had been a… bond between him and Sureblood. More delicate and indefinable than the bond between man and sword, but still there.

Of course, Adolin was the one who talked to his sword sometimes, so he had a habit of this sort of thing.

“I’m sorry,” Adolin said. “I know the two of you liked to run together. And… I don’t know if Father will be able to get down as much to see you. He’d already been withdrawing from battle before he got all these new responsibilities. I thought I’d stop by once in a while.”

The horse snorted loudly.

“Not to ride you,” Adolin said, reading indignation in the Ryshadium’s motions. “I just thought it might be nice for both of us.”

The horse poked his snout at Adolin’s satchel until he dug out another sugar cube. It seemed like agreement to Adolin, who fed the horse, then leaned back against the wall and watched him gallop through the pasture.

Showing off Adolin thought with amusement as Gallant pranced past him. Maybe Gallant would let him brush his coat. That would feel good, like the evenings he’d spent with Sureblood in the dark calm of the stables. At least, that was what he’d done before everything had gotten busy, with Shallan and the duels and everything else.

He’d ignored the horse right up until he’d needed Sureblood in battle. And then, in a flash of light, he was gone.

Adolin took a deep breath. Everything seemed insane these days. Not just Sureblood, but what he’d done to Sadeas, and now the investigation…

Watching Gallant seemed to help a little. Adolin was still there, leaning against the wall, when Renarin arrived. The younger Kholin poked his head through the doorway, looking around. He didn’t shy away when Gallant galloped past, but he did regard the stallion with wariness.

“Hey,” Adolin said from the side.

“Hey. Bashin said you were down here.”

“Just checking on Gallant,” Adolin said. “Because Father’s been so busy lately.”

Renarin approached. “You could ask Shallan to draw Sureblood,” Renarin said. “I bet, um, she’d be able to do a good job. To remember.”

It wasn’t a bad suggestion, actually. “Were you looking for me, then?”

“I…” Renarin watched Gallant as the horse pranced by again. “He’s excited.”

“He likes an audience.”

“They don’t fit, you know.”

“Don’t fit?”

“Ryshadium have stone hooves,” Renarin said, “stronger than ordinary horses’. Never need to be shod.”

“And that makes them not fit? I’d say that makes them fit better.…” Adolin eyed Renarin. “You mean ordinary horses, don’t you?”

Renarin blushed, then nodded. People had trouble following him sometimes, but that was merely because he tended to be so thoughtful. He’d be thinking about something deep, something brilliant, and then would only mention a part. It made him seem erratic, but once you got to know him, you realized he wasn’t trying to be esoteric. His lips just sometimes failed to keep up with his brain.

“Adolin,” he said softly. “I… um… I have to give you back the Shardblade you won for me.”

“Why?” Adolin said.

“It hurts to hold,” Renarin said. “It always has, to be honest. I thought it was just me, being strange. But it’s all of us.”

“Radiants, you mean.”

He nodded. “We can’t use the dead Blades. It’s not right.”

“Well, I suppose I could find someone else to use it,” Adolin said, running through options. “Though you should really be the one to choose. By right of bestowal, the Blade is yours, and you should pick the successor.”

“I’d rather you do it. I’ve given it to the ardents already, for safekeeping.”

“Which means you’ll be unarmed,” Adolin said.

Renarin glanced away.

“Or not,” Adolin said, then poked Renarin in the shoulder. “You’ve got a replacement already, don’t you.”

Renarin blushed again.

“You mink!” Adolin said. “You’ve managed to create a Radiant Blade? Why didn’t you tell us?”

“It just happened. Glys wasn’t certain he could do it… but we need more people to work the Oathgate… so…”

He took a deep breath, then stretched his hand to the side and summoned a long glowing Shardblade. Thin, with almost no crossguard, it had waving folds to the metal, like it had been forged.

“Gorgeous,” Adolin said. “Renarin, it’s fantastic!”

“Thanks.”

“So why are you embarrassed?”

“I’m… not?”

Adolin gave him a flat stare.

Renarin dismissed the Blade. “I simply… Adolin, I was starting to fit in. With Bridge Four, with being a Shardbearer. Now, I’m in the darkness again. Father expects me to be a Radiant, so I can help him unite the world. But how am I supposed to learn?”

Adolin scratched his chin with his good hand. “Huh. I assumed that it just kind of came to you. It hasn’t?”

“Some has. But it… frightens me, Adolin.” He held up his hand, and it started to glow, wisps of Stormlight trailing off it, like smoke from a fire. “What if I hurt someone, or ruin things?”

“You’re not going to,” Adolin said. “Renarin, that’s the power of the Almighty himself.”

Renarin only stared at that glowing hand, and didn’t seem convinced. So Adolin reached out with his good hand and took Renarin’s, holding it.

“This is good,” Adolin said to him. “You’re not going to hurt anyone. You’re here to save us.”

Renarin looked to him, then smiled. A pulse of Radiance washed through Adolin, and for an instant he saw himself perfected. A version of himself that was somehow complete and whole, the man he could be.

It was gone in a moment, and Renarin pulled his hand free and murmured an apology. He mentioned again the Shardblade needing to be given away, then fled back into the tower.

Adolin stared after him. Gallant trotted up and nudged him for more sugar, so he reached absently into his satchel and fed the horse.

Only after Gallant trotted off did Adolin realize he’d used his right hand.

He held it up, amazed, moving his fingers. His wrist had been completely healed.

Chapter 11

The Rift

THIRTY-THREE YEARS AGO

Dalinar danced from one foot to the other in the morning mist, feeling a new power, an energy in every step. Shardplate. His own Shardplate.

The world would never be the same place. They’d all expected he would someday have his own Plate or Blade, but he’d never been able to quiet the whisper of uncertainty from the back of his mind. What if it never happened?

But it had. Stormfather, it had. He’d won it himself, in combat. Yes, that combat had involved kicking a man off a cliff, but he’d defeated a Shardbearer regardless.

He couldn’t help but bask in how grand it felt.

“Calm, Dalinar,” Sadeas said from beside him in the mist. Sadeas wore his own golden Plate. “Patience.”

“It won’t do any good, Sadeas,” Gavilar—clad in bright blue Plate— said from Dalinar’s other side. All three of them wore their faceplates up for the moment. “The Kholin boys are chained axehounds, and we smell blood. We can’t go into battle breathing calming breaths, centered and serene, as the ardents teach.”

Dalinar shifted, feeling the cold morning fog on his face. He wanted to dance with the anticipationspren whipping in the air around him. Behind, the army waited in disciplined ranks, their footsteps, clinkings, coughs, and murmured banter rising through the fog.

He almost felt as if he didn’t need that army. He wore a massive hammer on his back, so heavy an unaided man—even the strongest of them— wouldn’t be able to lift it. He barely noticed the weight. Storms, this power. It felt remarkably like the Thrill.

“Have you given thought to my suggestion, Dalinar?” Sadeas asked.

“No.”

Sadeas sighed.

“If Gavilar commands me,” Dalinar said, “I’ll marry.”

“Don’t bring me into this,” Gavilar said. He summoned and dismissed his Shardblade repeatedly as they talked.

“Well,” Dalinar said, “until you say something, I’m staying single.” The only woman he’d ever wanted belonged to Gavilar. They’d married—storms, they had a child now. A little girl.

His brother must never know how Dalinar felt.

“But think of the benefit, Dalinar,” Sadeas said. “Your wedding could bring us alliances, Shards. Perhaps you could win us a princedom—one we wouldn’t have to storming drive to the brink of collapse before they join us!”

After two years of fighting, only four of the ten princedoms had accepted Gavilar’s rule—and two of those, Kholin and Sadeas, had been easy. The result was a united Alethkar: against House Kholin.

Gavilar was convinced that he could play them off one another, that their natural selfishness would lead them to stab one another in the back. Sadeas, in turn, pushed Gavilar toward greater brutality. He claimed that the fiercer their reputation, the more cities would turn to them willingly rather than risk being pillaged.

“Well?” Sadeas asked. “Will you at least consider a union of political necessity?”

“Storms, you still on that?” Dalinar said. “Let me fight. You and my brother can worry about politics.”

“You can’t escape this forever, Dalinar. You realize that, right? We’ll have to worry about feeding the darkeyes, about city infrastructure, about ties with other kingdoms. Politics.”

“You and Gavilar,” Dalinar said.

“All of us,” Sadeas said. “All three.”

“Weren’t you trying to get me to relax?” Dalinar snapped. Storms.

The rising sun finally started to disperse the fog, and that let him see their target: a wall about twelve feet high. Beyond that, nothing. A flat rocky expanse, or so it appeared. The chasm city was difficult to spot from this direction. Named Rathalas, it was also known as the Rift: an entire city that had been built inside a rip in the ground.

“Brightlord Tanalan is a Shardbearer, right?” Dalinar asked.

Sadeas sighed, lowering his faceplate. “We only went over this four times, Dalinar.”

“I was drunk. Tanalan. Shardbearer?”

“Blade only, Brother,” Gavilar said.

“He’s mine,” Dalinar whispered.

Gavilar laughed. “Only if you find him first! I’ve half a mind to give that Blade to Sadeas. At least he listens in our meetings.”

“All right,” Sadeas said. “Let’s do this carefully. Remember the plan. Gavilar, you—”

Gavilar gave Dalinar a grin, slammed his faceplate down, then took off running to leave Sadeas midsentence. Dalinar whooped and joined him, Plated boots grinding against stone.

Sadeas cursed loudly, then followed. The army remained behind for the moment.

Rocks started falling; catapults from behind the wall hurled solitary boulders or sprays of smaller rocks. Chunks slammed down around Dalinar, shaking the ground, causing rockbud vines to curl up. A boulder struck just ahead, then bounced, spraying chips of stone. Dalinar skidded past it, the Plate lending a spring to his motion. He raised his arm before his eye slit as a hail of arrows darkened the sky.

“Watch the ballistas!” Gavilar shouted.

Atop the wall, soldiers aimed massive crossbowlike devices mounted to the stone. One sleek bolt—the size of a spear—launched directly at Dalinar, and it proved far more accurate than the catapults. He threw himself to the side, Plate grinding on stone as he slid out of the way. The bolt hit the ground with such force that the wood shattered.

Other shafts trailed netting and ropes, hoping to trip a Shardbearer and render him prone for a second shot. Dalinar grinned, feeling the Thrill awaken within him, and recovered his feet. He leaped over a bolt trailing netting.

Tanalan’s men delivered a storm of wood and stone, but it wasn’t nearly enough. Dalinar took a stone in the shoulder and lurched, but quickly regained his momentum. Arrows were useless against him, the boulders too random, and the ballistas too slow to reload.

This was how it should be. Dalinar, Gavilar, Sadeas. Together. Other responsibilities didn’t matter. Life was about the fight. A good battle in the day—then at night, a warm hearth, tired muscles, and a good vintage of wine.

Dalinar reached the squat wall and leaped, propelling himself in a mighty jump. He gained just enough height to grab one of the crenels of the wall’s top. Men raised hammers to pound his fingers, but he hurled himself over the lip and onto the wall walk, crashing down amid panicked defenders. He jerked the release rope on his hammer—dropping it on an enemy behind—then swung out with his fist, sending men broken and screaming.

This was almost too easy! He seized his hammer, then brought it up and swung it in a wide arc, tossing men from the wall like leaves before a gust of wind. Just beyond him, Sadeas kicked over a ballista, destroying the device with a casual blow. Gavilar attacked with his Blade, dropping corpses by the handful, their eyes burning. Up here, the fortification worked against the defenders, leaving them cramped and clumped up—perfect for Shardbearers to destroy.

Dalinar surged through them, and in a few moments likely killed more men than he had in his entire life. At that, he felt a surprising yet profound dissatisfaction. This was not about his skill, his momentum, or even his reputation. You could have replaced him with a toothless gaffer and produced practically the same result.

He gritted his teeth against that sudden useless emotion. He dug deeply within, and found the Thrill waiting. It filled him, driving away dissatisfaction. Within moments he was roaring his pleasure. Nothing these men did could touch him. He was a destroyer, a conqueror, a glorious maelstrom of death. A god.

Sadeas was saying something. The silly man gestured in his golden Shardplate. Dalinar blinked, looking out over the wall. He could see the Rift proper from this vantage, a deep chasm in the ground that hid an entire city, built up the sides of either cliff

“Catapults, Dalinar!” Sadeas said. “Bring down those catapults!”

Right. Gavilar’s armies had started to charge the walls. Those catapults—near the way down into the Rift proper—were still launching stones, and would drop hundreds of men.

Dalinar leaped for the edge of the wall and grabbed a rope ladder to swing down. The ropes, of course, immediately snapped, sending him toppling to the ground. He struck with a crash of Plate on stone. It didn’t hurt, but his pride took a serious blow. Above, Sadeas looked at him over the edge. Dalinar could practically hear his voice.

Always rushing into things. Take some time to think once in a while, won’t you?

That had been a flat-out greenvine mistake. Dalinar growled and climbed to his feet, searching for his hammer. Storms! He’d bent the handle in his fall. How had he done that? It wasn’t made of the same strange metal as Blades and Plate, but it was still good steel.

Soldiers guarding the catapults swarmed toward him while the shadows of boulders passed overhead. Dalinar set his jaw, the Thrill saturating him, and reached for a stout wooden door set into the wall nearby. He ripped it free, the hinges popping, and stumbled. It came off more easily than he’d expected.

There was more to this armor than he’d ever imagined. Maybe he wasn’t any better with the Plate than some old gaffer, but he would change that. At that moment, he determined that he’d never be surprised again. He’d wear this Plate morning and night—he’d sleep in the storming stuff—until he was more comfortable in it than out.

He raised the wooden door and swung it like a bludgeon, sweeping soldiers away and opening a path to the catapults. Then he dashed forward and grabbed the side of one catapult. He ripped its wheel off, splintering wood and sending the machine teetering. He stepped onto it, grabbing the catapult’s arm and breaking it free.

Only ten more to go. He stood atop the wrecked machine when he heard a distant voice call his name. “Dalinar!”

He looked toward the wall, where Sadeas reached back and heaved his Shardbearer’s hammer. It spun in the air before slamming into the catapult next to Dalinar, wedging itself into the broken wood.

Sadeas raised a hand in salute, and Dalinar waved back in gratitude, then grabbed the hammer. The destruction went a lot faster after that. He pounded the machines, leaving behind shattered wood. Engineers—many of them women—scrambled away, screaming, “Blackthorn, Blackthorn!”

By the time he neared the last catapult, Gavilar had secured the gates and opened them to his soldiers. A flood of men entered, joining those who had scaled the walls. The last of the enemies near Dalinar fled down into the city, leaving him alone. He grunted and kicked the final broken catapult, sending it rolling backward across the stone toward the edge of the Rift.

It tipped, then fell over. Dalinar stepped forward, walking onto a kind of observation post, a section of rock with a railing to prevent people from slipping over the side. From this vantage, he got his first good look down at the city.

“The Rift” was a fitting name. To his right, the chasm narrowed, but here at the middle he’d have been hard-pressed to throw a stone across to the other side, even with Shardplate. And within it, there was life. Gardens bobbing with lifespren. Buildings built practically on top of one another down the V-shaped cliff sides. The place teemed with a network of stilts, bridges, and wooden walkways.

Dalinar turned and looked back at the wall that ran in a wide circle around the opening of the Rift on all sides except the west, where the canyon continued until it opened up below at the shores of the lake.

To survive in Alethkar, you had to find shelter from the storms. A wide cleft like this one was perfect for a city. But how did you protect it? Any attacking enemy would have the high ground. Many cities walked a risky line between security from storms and security from men.

Dalinar shouldered Sadeas’s hammer as groups of Tanalan’s soldiers flooded down from the walls, forming up to flank Gavilar’s army on both right and left. They’d try to press against the Kholin troops from both sides, but with three Shardbearers to face, they were in trouble. Where was Highlord Tanalan himself ?

Behind, Thakka approached with a small squad of elites, joining Dalinar on the stone viewing platform. Thakka put his hands on the railing, whistling softly.

“Something’s going on with this city,” Dalinar said.

“What?”

“I don’t know.…” Dalinar might not pay attention to the grand plans Gavilar and Sadeas made, but he was a soldier. He knew battlefields like a woman knew her mother’s recipes: he might not be able to give you measurements, but he could taste when something was off.

The fighting continued behind him, Kholin soldiers clashing with Tanalan’s defenders. Tanalan’s armies didn’t fare well; demoralized by the advancing Kholin army, the enemy ranks quickly broke and scrambled into a retreat, clogging the ramps down into the city. Gavilar and Sadeas didn’t give chase; they had the high ground now. No need to rush into a potential ambush.

Gavilar clomped across the stone, Sadeas beside him. They’d want to survey the city and rain arrows upon those below—maybe even use stolen catapults, if Dalinar had left any functional. They’d siege this place until it broke.

Three Shardbearers, Dalinar thought. Tanalan has to be planning to deal with us somehow.…

This viewing platform was the best vantage for looking into the city. And they’d situated the catapults right next to it—machines that the Shardbearers were certain to attack and disable. Dalinar glanced to the sides, and saw cracks in the stone floor of the viewing platform.

“No!” Dalinar shouted to Gavilar. “Stay back! It’s a—”

The enemy must have been watching, for the moment he shouted, the ground fell out from beneath him. Dalinar caught a glimpse of Gavilar— held back by Sadeas—looking on in horror as Dalinar, Thakka, and a handful of other elites were toppled into the Rift.

Storms. The entire section of stone where they’d been standing—the lip hanging out over the Rift—had broken free! As the large section of rock tumbled down into the first buildings, Dalinar was flung into the air above the city. Everything spun around him.

A moment later, he crashed into a building with an awful crunch. Something hard hit his arm, an impact so powerful he heard his armor there shatter.

The building failed to stop him. He tore right through the wood and continued, helm grinding against stone as he somehow came in contact with the side of the Rift.

He hit another surface with a loud crunch, and blessedly here he finally stopped. He groaned, feeling a sharp pain from his left hand. He shook his head, and found himself staring upward some fifty feet through a shattered section of the near-vertical wooden city. The large section of falling rock had torn a swath through the city along the steep incline, smashing homes and walkways. Dalinar had been flung just to the north, and had eventually come to rest on the wooden roof of a building.

He didn’t see signs of his men. Thakka, the other elites. But without Shardplate… He growled, angerspren boiling around him like pools of blood. He shifted on the rooftop, but the pain in his hand made him wince. His armor all down his left arm had shattered, and in falling he appeared to have broken a few fingers.

His Shardplate leaked glowing white smoke from a hundred fractures, but the only pieces he’d lost completely were from his left arm and hand.

He gingerly pried himself from the rooftop, but as he shifted, he broke through and fell into the home. He grunted as he hit, members of a family screaming and pulling back against the wall. Tanalan apparently hadn’t told the people of his plan to crush a section of his own city in a desperate attempt to deal with the enemy Shardbearers.

Dalinar got to his feet, ignoring the cowering people, and shoved open the door—breaking it with the strength of his push—and stepped out onto a wooden walkway that ran before the homes on this tier of the city.

A hail of arrows immediately fell on him. He turned his right shoulder toward them, growling, shielding his eye slit as best he could while he inspected the source of the attack. Fifty archers were set up on a garden platform on the other storming side of the Rift from him. Wonderful.

He recognized the man leading the archers. Tall, with an imperious bearing and stark white plumes on his helm. Who put chicken feathers on their helms? Looked ridiculous. Well, Tanalan was a fine enough fellow. Dalinar had beat him once at pawns, and Tanalan had paid the bet with a hundred glowing bits of ruby, each dropped into a corked bottle of wine. Dalinar had always found that amusing.

Reveling in the Thrill, which rose in him and drove away pain, Dalinar charged along the walkway, ignoring arrows. Above, Sadeas was leading a force down one of the ramps outside the path of the rockfall, but it would be slow going. By the time they arrived, Dalinar intended to have a new Shardblade.

He charged onto one of the bridges that crossed the Rift. Unfortunately, he knew exactly what he would do if preparing this city for an assault. Sure enough, a pair of soldiers hurried down the other side of the Rift, then used axes to attack the support posts to Dalinar’s bridge. It had Soulcast metal ropes holding it up, but if they could get those posts down—dropping the lines—his weight would surely cause the entire thing to fall.

The bottom wash of the Rift was easily another hundred feet below. Growling, Dalinar made the only choice he could. He threw himself over the side of his walkway, dropping a short distance to one below. It looked sturdy enough. Even so, one foot smashed through the wooden planks, nearly followed by his entire body.

He heaved himself up and continued running across. Two more soldiers reached the posts holding up this bridge, and they began frantically hacking away.

The walkway shook beneath Dalinar’s feet. Stormfather. He didn’t have much time, but there were no more walkways within jumping distance. Dalinar pushed himself to a run, roaring, his footfalls cracking boards.

A single black arrow fell from above, swooping like a skyeel. It dropped one of the soldiers. Another arrow followed, hitting the second soldier even as he gawked at his fallen ally. The walkway stopped shaking, and Dalinar grinned, pulling to a stop. He turned, spotting a man standing near the sheared-off section of stone above. He lifted a black bow toward Dalinar.

“Teleb, you storming miracle,” Dalinar said.

He reached the other side and plucked an axe from the hands of a dead man. Then he charged up a ramp toward where he’d seen Highlord Tanalan.

He found the place easily, a wide wooden platform built on struts connected to parts of the wall below, and draped with vines and blooming rockbuds. Lifespren scattered as Dalinar reached it.

Centered in the garden, Tanalan waited with a force of some fifty soldiers. Puffing inside his helm, Dalinar stepped up to confront them. Tanalan was armored in simple steel, no Shardplate, though a brutal-looking Shardblade—wide, with a hooked tip—appeared in his grasp.

Tanalan barked for his soldiers to stand back and lower their bows. Then he strode toward Dalinar, holding the Shardblade with both hands.

Everyone always fixated upon Shardblades. Specific weapons had lore dedicated to them, and people traced which kings or brightlords had carried which sword. Well, Dalinar had used both Blade and Plate, and if given the choice of one, he’d pick Plate every time. All he needed to do was get in one solid hit on Tanalan, and the fight would be over. The highlord, however, had to contend with a foe who could resist his blows.

The Thrill thrummed inside Dalinar. Standing between two squat trees, he set his stance, keeping his exposed left arm pointed away from the highlord while gripping the axe in his gauntleted right hand. Though it was a war axe, it felt like a child’s plaything.

“You should not have come here, Dalinar,” Tanalan said. His voice bore a distinctively nasal accent common to this region. The Rifters always had considered themselves a people apart. “We had no quarrel with you or yours.”

“You refused to submit to the king,” Dalinar said, armor plates clinking as he rounded the highlord while trying to keep an eye on the soldiers. He wouldn’t put it past them to attack him once he was distracted by the duel. It was what he himself would have done.

“The king?” Tanalan demanded, angerspren boiling up around him. “There hasn’t been a throne in Alethkar for generations. Even if we were to have a king again, who is to say the Kholins deserve the mantle?”

“The way I see it,” Dalinar said, “the people of Alethkar deserve a king who is the strongest and most capable of leading them in battle. If only there were a way to prove that.” He grinned inside his helm.

Tanalan attacked, sweeping in with his Shardblade and trying to leverage his superior reach. Dalinar danced back, waiting for his moment. The Thrill was a heady rush, a lust to prove himself.

But he needed to be cautious. Ideally Dalinar would prolong this fight, relying on his Plate’s superior strength and the stamina it provided. Unfortunately, that Plate was still leaking, and he had all these guards to deal with. Still, he tried to play it as Tanalan would expect, dodging attacks, acting as if he were going to drag out the fight.

Tanalan growled and came in again. Dalinar blocked the blow with his arm, then made a perfunctory swing with his axe. Tanalan dodged back easily. Stormfather, that Blade was long. Almost as tall as Dalinar was.

Dalinar maneuvered, brushing against the foliage of the garden. He couldn’t even feel the pain of his broken fingers anymore. The Thrill called to him.

Wait. Act like you’re drawing this out as long as possible.…

Tanalan advanced again, and Dalinar dodged backward, faster because of his Plate. And then when Tanalan tried his next strike, Dalinar ducked toward him.

He deflected the Shardblade with his arm again, but this blow hit hard, shattering the arm plate. Still, Dalinar’s surprise rush let him lower his shoulder and slam it against Tanalan. The highlord’s armor clanged, bending before the force of the Shardplate, and the highlord tripped.

Unfortunately, Dalinar was off balance just enough from his rush to fall alongside the highlord. The platform shook as they hit the ground, the wood cracking and groaning. Damnation! Dalinar had not wanted to go to the ground while surrounded by foes. Still, he had to stay inside the reach of that Blade.

Dalinar dropped off his right gauntlet—without the arm piece connecting it to the rest of the armor, it was dead weight—as the two of them twisted in a heap. He’d lost the axe, unfortunately. The highlord battered against Dalinar with the pommel of his sword, to no effect. But with one hand broken and the other lacking the power of Plate, Dalinar couldn’t get a good hold on his foe.

Dalinar rolled, finally positioning himself above Tanalan, where the weight of the Shardplate would keep his foe pinned. At that moment though, the other soldiers attacked. Just as he’d expected. Honorable duels like this—on a battlefield at least—always lasted only until your lighteyes was losing.

Dalinar rolled free. The soldiers obviously weren’t ready for how quickly he responded. He got to his feet and scooped up his axe, then lashed out. His right arm still had the pauldron and down to the elbow brace, so when he swung, he had power—a strange mix of Shard-enhanced strength and frailty from his exposed arms. He had to be careful not to snap his own wrist.

He dropped three men with a flurry of axe slices. The others backed away, blocking him with polearms as their fellows helped Tanalan to his feet.

“You speak of the people,” Tanalan said hoarsely, gauntleted hand feeling at his chest where the cuirass had been bent significantly by Dalinar’s rush. He seemed to be having trouble breathing. “As if this were about them. As if it were for their good that you loot, you pillage, you murder. You’re an uncivilized brute.”

“You can’t civilize war,” Dalinar said. “There’s no painting it up and making it pretty.”

“You don’t have to pull sorrow behind you like a sledge on the stones, scraping and crushing those you pass. You’re a monster.”

“I’m a soldier,” Dalinar said, eyeing Tanalan’s men, many of whom were preparing their bows.

Tanalan coughed. “My city is lost. My plan has failed. But I can do Alethkar one last service. I can take you down, you bastard.”

The archers started to loose.

Dalinar roared and threw himself to the ground, hitting the platform with the weight of Shardplate. The wood cracked around him, weakened by the fighting earlier, and he broke through it, shattering struts underneath.

The entire platform came crashing down around him, and together they fell toward the tier below. Dalinar heard screams, and he hit the next walkway hard enough to daze him, even with Shardplate.

Dalinar shook his head, groaning, and found his helm cracked right down the front, the uncommon vision granted by the armor spoiled. He pulled the helm free with one hand and gasped for breath. Storms, his good arm hurt too. He glanced at it and found splinters piercing his skin, including one chunk as long as a dagger.

He grimaced. Below, the few remaining soldiers who had been positioned to cut down bridges came charging up toward him.

Steady, Dalinar. Be ready!

He got to his feet, dazed, exhausted, but the two soldiers didn’t come for him. They huddled around Tanalan’s body where it had fallen from the platform above. The soldiers grabbed him, then fled.

Dalinar roared and awkwardly gave pursuit. His Plate moved slowly, and he stumbled through the wreckage of the fallen platform, trying to keep up with the soldiers.

The pain from his arms made him mad with rage. But the Thrill, the Thrill drove him forward. He would not be beaten. He would not stop! Tanalan’s Shardblade had not appeared beside his body. That meant his foe still lived. Dalinar had not yet won.

Fortunately, most of the soldiers had been positioned to fight on the other side of the city. This side was practically empty, save for huddled townspeople—he caught glimpses of them hiding in their homes.

Dalinar limped up ramps along the side of the Rift, following the men dragging their brightlord. Near the top, the two soldiers set their burden down beside an exposed portion of the chasm’s rock wall. They did something that caused a portion of that wall to open inward, revealing a hidden door. They towed their fallen brightlord into it, and two other soldiers—responding to their frantic calls—rushed out to meet Dalinar, who arrived moments later.

Helmless, Dalinar saw red as he engaged them. They bore weapons; he did not. They were fresh, and he had wounds nearly incapacitating both arms.

The fight still ended with the two soldiers on the ground, broken and bleeding. Dalinar kicked open the hidden door, Plated legs functioning enough to smash it down.

He lurched into a small tunnel with diamond spheres glowing on the walls. That door was covered in hardened crem on the outside, making it seem like a part of the wall. If he hadn’t seen them enter, it would have taken days, maybe weeks to locate this place.

At the end of a short walk, he found the two soldiers he’d followed. Judging by the blood trail, they’d deposited their brightlord in the closed room behind them.

They rushed Dalinar with the fatalistic determination of men who knew they were probably dead. The pain in Dalinar’s arms and head seemed nothing before the Thrill. He had rarely felt it so strong as he did now, a beautiful clarity, such a wonderful emotion.

He ducked forward, supernaturally quick, and used his shoulder to crush one soldier against the wall. The other fell to a well-placed kick, then Dalinar burst through the door beyond them.

Tanalan lay on the ground here, blood surrounding him. A beautiful woman was draped across him, weeping. Only one other person was in the small chamber: a young boy. Six, perhaps seven. Tears streaked the child’s face, and he struggled to lift his father’s Shardblade in two hands.

Dalinar loomed in the doorway.

“You can’t have my daddy,” the boy said, words distorted by his sorrow. Painspren crawled around the floor. “You can’t. You… you…” His voice fell to a whisper. “Daddy said… we fight monsters. And with faith, we will win.…”

A few hours later, Dalinar sat on the edge of the Rift, his legs swinging over the broken city below. His new Shardblade rested across his lap, his Plate—deformed and broken—in a heap beside him. His arms were bandaged, but he’d chased away the surgeons.

He stared out at what seemed an empty plain, then flicked his eyes toward the signs of human life below. Dead bodies in heaps. Broken buildings. Splinters of civilization.

Gavilar eventually walked up, trailed by two bodyguards from Dalinar’s elites, Kadash and Febin today. Gavilar waved them back, then groaned as he settled down beside Dalinar, removing his helm. Exhaustionspren spun overhead, though—despite his fatigue—Gavilar looked thoughtful. With those keen, pale green eyes, he’d always seemed to know so much. Growing up, Dalinar had simply assumed that his brother would always be right in whatever he said or did. Aging hadn’t much changed his opinion of the man.

“Congratulations,” Gavilar said, nodding toward the Blade. “Sadeas is irate it wasn’t his.”

“He’ll find one of his own eventually,” Dalinar said. “He’s too ambitious for me to believe otherwise.”

Gavilar grunted. “This attack nearly cost us too much. Sadeas is saying we need to be more careful, not risk ourselves and our Shards in solitary assaults.”

“Sadeas is smart,” Dalinar said. He reached gingerly with his right hand, the less mangled one, and raised a mug of wine to his lips. It was the only drug he cared about for the pain—and maybe it would help with the shame too. Both feelings seemed stark, now that the Thrill had receded and left him deflated.

“What do we do with them, Dalinar?” Gavilar asked, waving down toward the crowds of civilians the soldiers were rounding up. “Tens of thousands of people. They won’t be cowed easily; they won’t like that you killed their highlord and his heir. Those people will resist us for years. I can feel it.”

Dalinar took a drink. “Make soldiers of them,” he said. “Tell them we’ll spare their families if they fight for us. You want to stop doing a Shardbearer rush at the start of battles? Sounds like we’ll need some expendable troops.”

Gavilar nodded, considering. “Sadeas is right about other things too, you know. About us. And what we’re going to have to become.”

“Don’t talk to me about that.”

“Dalinar…”

“I lost half my elites today, my captain included. I’ve got enough problems.”

“Why are we here, fighting? Is it for honor? Is it for Alethkar?”

Dalinar shrugged.

“We can’t just keep acting like a bunch of thugs,” Gavilar said. “We can’t rob every city we pass, feast every night. We need discipline; we need to hold the land we have. We need bureaucracy, order, laws, politics.”

Dalinar closed his eyes, distracted by the shame he felt. What if Gavilar found out?

“We’re going to have to grow up,” Gavilar said softly.

“And become soft? Like these highlords we kill? That’s why we started, isn’t it? Because they were all lazy, fat, corrupt?”

“I don’t know anymore. I’m a father now, Dalinar. That makes me wonder about what we do once we have it all. How do we make a kingdom of this place?”

Storms. A kingdom. For the first time in his life, Dalinar found that idea horrifying.

Gavilar eventually stood up, responding to some messengers who were calling for him. “Could you,” he said to Dalinar, “at least try to be a little less foolhardy in future battles?”

“This coming from you?”

“A thoughtful me,” Gavilar said. “An… exhausted me. Enjoy Oathbringer. You earned it.”

“Oathbringer?”

“Your sword,” Gavilar said. “Storms, didn’t you listen to anything last night? That’s Sunmaker’s old sword.”

Sadees, the Sunmaker. He had been the last man to unite Alethkar, centuries ago. Dalinar shifted the Blade in his lap, letting the light play off the pristine metal.

“It’s yours now,” Gavilar said. “By the time we’re done, I’ll have it so that nobody even thinks of Sunmaker anymore. Just House Kholin and Alethkar.”

He walked away. Dalinar rammed the Shardblade into the stone and leaned back, closing his eyes again and remembering the sound of a brave boy crying.

Chapter 12

Negotiations

I ask not that you forgive me. Nor that you even understand.

—From Oathbringer, preface

Dalinar stood beside the glass windows in an upper-floor room of Urithiru, hands clasped behind his back. He could see his reflection hinted in the window, and beyond it vast openness. The sky cloud-free, the sun burning white.

Windows as tall as he was—he’d never seen anything like them. Who would dare build something of glass, so brittle, and face it toward the storms? But of course, this city was above the storms. These windows seemed a mark of defiance, a symbol of what the Radiants had meant. They had stood above the pettiness of world politics. And because of that height, they could see so far.…

You idealize them, said a distant voice in his head, like rumbling thunder. They were men like you. No better. No worse.

“I find that encouraging,” Dalinar whispered back. “If they were like us, then it means we can be like them.”

They eventually betrayed us. Do not forget that.

“Why?” Dalinar asked. “What happened? What changed them?”

The Stormfather fell silent.

“Please,” Dalinar said. “Tell me.”

Some things are better left forgotten, the voice said to him. You of all men should understand this, considering the hole in your mind and the person who once filled it.

Dalinar drew in a sharp breath, stung by the words.

“Brightlord,” Brightness Kalami said from behind. “The emperor is ready for you.”

Dalinar turned. Urithiru’s upper levels held several unique rooms, including this amphitheater. Shaped like a half-moon, the room had windows at the top—the straight side—then rows of seats leading down to a speaking floor below. Curiously, each seat had a small pedestal beside it. For the Radiant’s spren, the Stormfather told him.

Dalinar started down the steps toward his team: Aladar and his daughter, May. Navani, wearing a bright green havah, sitting in the front row with feet stretched out before her, shoes off and ankles crossed. Elderly Kalami to write, and Teshav Khal—one of Alethkar’s finest political minds—to advise. Her two senior wards sat beside her, ready to provide research or translation if needed.

A small group, prepared to change the world.

“Send my greetings to the emperor,” Dalinar instructed.

Kalami nodded, writing. Then she cleared her throat, reading the response that the spanreed—writing as if on its own—relayed. “You are greeted by His Imperial Majesty Ch.V.D. Yanagawn the First, Emperor of Makabak, King of Azir, Lord of the Bronze Palace, Prime Aqasix, grand minister and emissary of Yaezir.”

“An imposing title,” Navani noted, “for a fifteen-year-old boy.”

“He supposedly raised a child from the dead,” Teshav said, “a miracle that gained him the support of the viziers. Local word is that they had trouble finding a new Prime after the last two were murdered by our old friend the Assassin in White. So the viziers picked a boy with questionable lineage and made up a story about him saving someone’s life in order to demonstrate a divine mandate.”

Dalinar grunted. “Making things up doesn’t sound very Azish.”

“They’re fine with it,” Navani said, “as long as you can find witnesses willing to fill out affidavits. Kalami, thank His Imperial Majesty for meeting with us, and his translators for their efforts.”

Kalami wrote, and then she looked up at Dalinar, who began to pace the center of the room. Navani stood to join him, eschewing her shoes, walking in socks.

“Your Imperial Majesty,” Dalinar said, “I speak to you from the top of Urithiru, city of legend. The sights are breathtaking. I invite you to visit me here and tour the city. You are welcome to bring any guards or retinue you see fit.”

He looked to Navani, and she nodded. They’d discussed long how to approach the monarchs, and had settled on a soft invitation. Azir was first, the most powerful country in the west and home to what would be the most central and important of the Oathgates to secure.

The response took time. The Azish government was a kind of beautiful mess, though Gavilar had often admired it. Layers of clerics filled all levels— where both men and women wrote. Scions were kind of like ardents, though they weren’t slaves, which Dalinar found odd. In Azir, being a priestminister in the government was the highest honor to which one could aspire.

Traditionally, the Azish Prime claimed to be emperor of all Makabak—a region that included over a half-dozen kingdoms and princedoms. In reality, he was king over only Azir, but Azir did cast a long, long shadow.

As they waited, Dalinar stepped up beside Navani, resting his fingers on one of her shoulders, then drew them across her back, the nape of her neck, and let them linger on the other shoulder.

Who would have thought a man his age could feel so giddy?

“ ‘Your Highness,’ ” the reply finally came, Kalami reading the words. “ ‘We thank you for your warning about the storm that blew from the wrong direction. Your timely words have been noted and recorded in the official annals of the empire, recognizing you as a friend to Azir.’ ”

Kalami waited for more, but the spanreed stopped moving. Then the ruby flashed, indicating that they were done.

“That wasn’t much of a response,” Aladar said. “Why didn’t he reply to your invitation, Dalinar?”

“Being noted in their offi ial records is a great honor to the Azish,” Teshav said, “so they’ve paid you a compliment.”

“Yes,” Navani said, “but they are trying to dodge the offer we made. Press them, Dalinar.”

“Kalami, please send the following,” Dalinar said. “I am honored, though I wish my inclusion in your annals could have been due to happier circumstances. Let us discuss the future of Roshar together, here. I am eager to make your personal acquaintance.”

They waited as patiently as they could for a response. It finally came, in Alethi. “ ‘We of the Azish crown are saddened to share mourning for the fallen with you. As your noble brother was killed by the Shin destroyer, so were beloved members of our court. This creates a bond between us.’ ”

That was all.

Navani clicked her tongue. “They’re not going to be pushed into an answer.”

“They could at least explain themselves!” Dalinar snapped. “It feels like we’re having two different conversations!”

“The Azish,” Teshav said, “do not like to give offense. They’re almost as bad as the Emuli in that regard, particularly with foreigners.”

It wasn’t only an Azish attribute, in Dalinar’s estimation. It was the way of politicians worldwide. Already this conversation was starting to feel like his efforts to bring the highprinces to his side, back in the warcamps. Half answer after half answer, mild promises with no bite to them, laughing eyes that mocked him even while they pretended to be perfectly sincere.

Storms. Here he was again. Trying to unite people who didn’t want to listen to him. He couldn’t afford to be bad at this, not any longer.

There was a time, he thought, when I united in a different way. He smelled smoke, heard men screaming in pain. Remembered bringing blood and ash to those who defied his brother.

Those memories had become particularly vivid lately.

“Another tactic maybe?” Navani suggested. “Instead of an invitation, try an offer of aid.”

“Your Imperial Majesty,” Dalinar said. “War is coming; surely you have seen the changes in the parshmen. The Voidbringers have returned. I would have you know that the Alethi are your allies in this conflict. We would share information regarding our successes and failures in resisting this enemy, with hope that you will report the same to us. Mankind must be unified in the face of the mounting threat.”

The reply eventually came: “ ‘We agree that aiding one another in this new age will be of the utmost importance. We are glad to exchange information. What do you know of these transformed parshmen?’ ”

“We engaged them on the Shattered Plains,” Dalinar said, relieved to make some kind of headway. “Creatures with red eyes, and similar in many ways to the parshmen we found on the Shattered Plains—only more dangerous. I will have my scribes prepare reports for you detailing all we have learned in fighting the Parshendi over the years.”

“ ‘Excellent,’” the reply finally came. “ ‘This information will be extremely welcome in our current conflict.’ ”

“What is the status of your cities?” Dalinar asked. “What have the parshmen been doing there? Do they seem to have a goal beyond wanton destruction?”

Tensely, they waited for word. So far they’d been able to discover blessed little about the parshmen the world over. Captain Kaladin sent reports using scribes from towns he visited, but knew next to nothing. Cities were in chaos, and reliable information scarce.

“ ‘Fortunately,’ ” came the reply, “ ‘our city stands, and the enemy is not actively attacking any longer. We are negotiating with the hostiles.’ ”

“Negotiating?” Dalinar said, shocked. He turned to Teshav, who shook her head in wonder.

“Please clarify, Your Majesty,” Navani said. “The Voidbringers are willing to negotiate with you?”

“ ‘Yes,’ ” came the reply. “ ‘We are exchanging contracts. They have very detailed demands, with outrageous stipulations. We hope that we can forestall armed conflict in order to gather ourselves and fortify the city.’ ”

“They can write?” Navani pressed. “The Voidbringers themselves are sending you contracts?”

“ ‘The average parshman cannot write, so far as we can tell,’ ” the reply came. “ ‘But some are different—stronger, with strange powers. They do not speak like the others.’ ”

“Your Majesty,” Dalinar said, stepping up to the spanreed writing table, speaking more urgently—as if the emperor and his ministers could hear his passion through the written word. “I need to talk to you directly. I can come myself, through the portal we wrote of earlier. We must get it working again.”

Silence. It stretched so long that Dalinar found himself grinding his teeth, itching to summon a Shardblade and dismiss it, over and over, as had been his habit as a youth. He’d picked it up from his brother.

A response finally came. “ ‘We regret to inform you that the device you mention,’ ” Kalami read, “ ‘is not functional in our city. We have investigated it, and have found that it was destroyed long ago. We cannot come to you, nor you to us. Many apologies.’ ”

“He’s telling us this now?” Dalinar said. “Storms! That’s information we could have used as soon as he learned it!”

“It’s a lie,” Navani said. “The Oathgate on the Shattered Plains functioned after centuries of storms and crem buildup. The one in Azimir is a monument in the Grand Market, a large dome in the center of the city.”

Or so she’d determined from maps. The one in Kholinar had been incorporated into the palace structure, while the one in Thaylen City was some kind of religious monument. A beautiful relic like this wouldn’t simply be destroyed.

“I agree with Brightness Navani’s assessment,” Teshav said. “They are worried about the idea of you or your armies visiting. This is an excuse.” She frowned, as if the emperor and his ministers were little more than spoiled children disobeying their tutors.

The spanreed started writing again.

“What does it say?” Dalinar said, anxious.

“It’s an affidavit,” Navani said, amused. “That the Oathgate is not functional, signed by imperial architects and stormwardens.” She read further. “Oh, this is delightful. Only the Azish would assume you’d want certification that something is broken.”

“Notably,” Kalami added, “it only certifies that the device ‘does not function as a portal.’ But of course it would not, not unless a Radiant were to visit and work it. This affidavit basically says that when turned off, the device doesn’t work.”

“Write this, Kalami,” Dalinar said. “Your Majesty. You ignored me once. Destruction caused by the Everstorm was the result. Please, this time listen. You cannot negotiate with the Voidbringers. We must unify, share information, and protect Roshar. Together.”

She wrote it and Dalinar waited, hands pressed against the table.

“ ‘We misspoke when we mentioned negotiations,’” Kalami read. “ ‘It was a mistake of translation. We agree to share information, but time is short right now. We will contact you again to further discuss. Farewell, Highprince Kholin.’”

“Bah!” Dalinar said, pushing himself back from the table. “Fools, idiots! Storming lighteyes and Damnation’s own politics!” He stalked across the room, wishing he had something to kick, before forcing his temper under control.

“That’s more of a stonewall than I expected,” Navani said, folding her arms. “Brightness Khal?”

“In my experiences with the Azish,” Teshav said, “they are extremely proficient at saying very little in as many words as possible. This is not an unusual example of communication with their upper ministers. Don’t be put off; it will take time to accomplish anything with them.”

“Time during which Roshar burns,” Dalinar said. “Why did they pull back regarding their claim to have had negotiations with the Voidbringers? Are they thinking of allying themselves to the enemy?”

“I hesitate to guess,” Teshav said. “But I would say that they simply decided they’d given away more information than intended.”

“We need Azir,” Dalinar said. “Nobody in Makabak will listen to us unless we have Azir’s blessing, not to mention that Oathgate.…” He trailed off as a different spanreed on the table started blinking.

“It’s the Thaylens,” Kalami said. “They’re early.”

“You want to reschedule?” Navani asked.

Dalinar shook his head. “No, we can’t afford to wait another few days before the queen can spare time again.” He took a deep breath. Storms, talking to politicians was more exhausting than a hundred-mile march in full armor. “Proceed, Kalami. I’ll contain my frustration.”

Navani settled down on one of the seats, though Dalinar remained standing. Light poured in through the windows, pure and bright. It flowed down, bathing him. He breathed in, almost feeling as if he could taste the sunlight. He’d spent too many days inside the twisting stone corridors of Urithiru, lit by the frail light of candles and lamps.

“ ‘Her Royal Highness,’ ” Kalami read, “ ‘Brightness Fen Rnamdi, queen of Thaylenah, writes to you.’ ” Kalami paused. “Brightlord… pardon the interruption, but that indicates that the queen holds the spanreed herself rather than using a scribe.”

To another woman, that would have been intimidating. To Kalami, it was merely one of many footnotes—which she added copiously to the bottom of the page before preparing the reed to relay Dalinar’s words.

“Your Majesty,” Dalinar said, clasping his hands behind his back and pacing the stage at the center of the seats. Do better. Unite them. “I send you greetings from Urithiru, holy city of the Knights Radiant, and extend to you our humblest invitation. This tower is truly a sight to behold, matched only by the glory of a sitting monarch. I would be honored to present it for you to experience.”

The spanreed quickly scribbled a reply. Queen Fen was writing directly in Alethi. “ ‘Kholin,’ ” Kalami read, “ ‘you old brute. Quit spreading chull scat. What do you really want?’ ”

“I always did like her,” Navani noted.

“I’m being sincere, Your Majesty,” Dalinar said. “My only desire is for us to meet in person, and to talk to you and show you what we’ve discovered. The world is changing around us.”

“ ‘Oh,’ ” came the reply, “ ‘the world is changing, is it? What led you to this incredible conclusion? Was it the fact that our slaves suddenly became Voidbringers, or was it perhaps the storm that blew the wrong way,’—She wrote that twice as large as the line around it, Brightlord—‘ripping our cities apart?’ ”

Aladar cleared his throat. “Her Majesty seems to be having a bad day.”

“She’s insulting us,” Navani said. “For Fen, that actually implies a good day.”

“She’s always been perfectly civil the few times I’ve met her,” Dalinar said with a frown.

“She was being queenly then,” Navani said. “You’ve got her talking to you directly. Trust me, it’s a good sign.”

“Your Majesty,” Dalinar said, “please tell me of your parshmen. The transformation came upon them?”

“ ‘Yes,’ ” she replied. “ ‘Storming monsters stole our best ships—almost everything in the harbor from single-masted sloops on up—and escaped the city.’ ”

“They… sailed?” Dalinar said, again shocked. “Confirm. They didn’t attack?”

“ ‘There were some scuffles,’ ” Fen wrote, “ ‘but most everyone was too busy dealing with the eff cts of the storm. By the time we got things somewhat sorted out, they were sailing away in a grand fleet of royal warships and private trading vessels alike.’ ”

Dalinar drew a breath. We don’t know half as much about the Voidbringers as we assumed. “Your Majesty,” he continued. “You might remember that we warned you about the imminent arrival of that storm.”

“ ‘I believed you,’ ” Fen said. “ ‘If only because we got word from New Natanan confirming it. We tried to prepare, but a nation cannot upend four millennia worth of tradition at a snap of the fingers. Thaylen City is a shambles, Kholin. The storm broke our aqueducts and sewer systems, and ripped apart our docks—flattened the entire outer market! We have to fix all our cisterns, reinforce our buildings to withstand storms, and rebuild society—all without any parshman laborers and in the middle of the storming Weeping. I don’t have time for sightseeing.’ ”

“It’s hardly sightseeing, Your Majesty,” Dalinar said. “I am aware of your problems, and dire though they are, we cannot ignore the Voidbringers. I intend to convene a grand conference of kings to fight this threat.”

“ ‘Led by you,’ ” Fen wrote in reply. “ ‘Of course.’ ”

“Urithiru is the natural location for a meeting,” Dalinar said. “Your Majesty, the Knights Radiant have returned—we speak again their ancient oaths, and bind the Surges of nature to us. If we can restore your Oathgate to functionality, you can be here in an afternoon, then return the same evening to direct the needs of your city.”

Navani nodded at this tactic, though Aladar folded his arms, looking thoughtful.

“What?” Dalinar asked him as Kalami wrote.

“We need a Radiant to travel to the city to activate their Oathgate, right?” Aladar asked.

“Yes,” Navani said. “A Radiant needs to unlock the gate on this side— which we can do at any moment—then one has to travel to the destination city and undo the lock there as well. That done, a Radiant can initiate a transfer from either location.”

“Then the only one we have that can theoretically get to Thaylen City is the Windrunner,” Aladar said. “But what if it takes him months to get back here? Or what if he’s captured by the enemy? Can we even make good on our promises, Dalinar?”

A troubling problem, but one that Dalinar thought he might have an answer to. There was a weapon that he’d decided to keep hidden for now. It might work as well as a Radiant’s Shardblade in opening the Oathgates— and might let someone reach Thaylen City by flight.

That was moot for the time being. First he needed a willing ear on the other side of the spanreed.